Check out Part I Here.

Jim Collins brings the characteristics of the 20 Mile March to life through the distinct stories and strategies of the explorers Amundsen and Scott, who each sought to be the first to the South Pole. Through the juxtaposition of their journeys, Collins outlines the important details related to achieving specific, measurable goals, no matter the circumstances.

I began to see positive effects when implementing Collins’ concepts. So, as it often does, my mind went to education and applying the idea there. Almost everyone I talk to can agree we need change in our education system. Different initiatives, programs, and platforms are started in the eduworld with lots of energy and excitement, only to be abandoned or changed with the passing of each year. Whether it is an individual student goal or a large systemic shift, there is power in planning with the 20 mile march in mind.

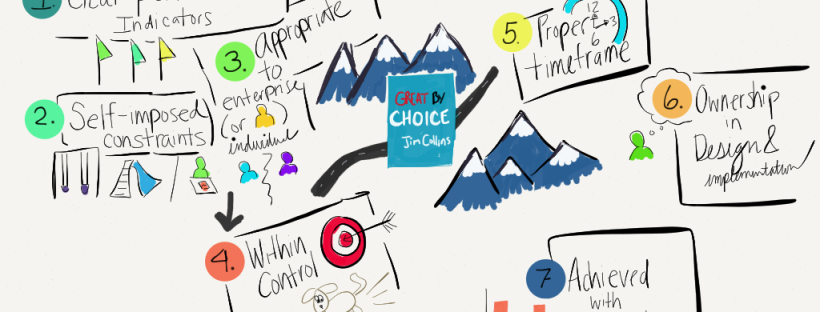

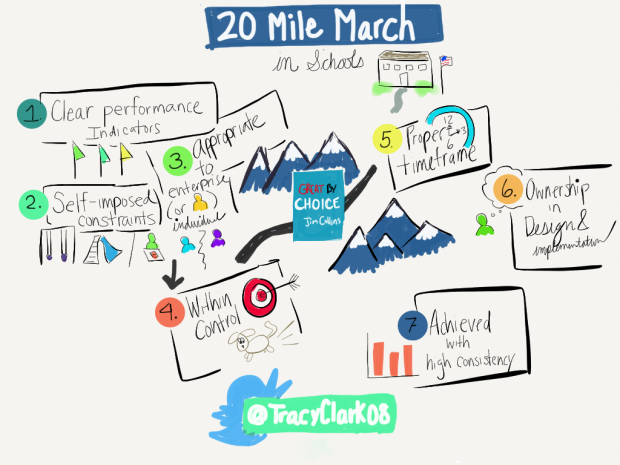

7 Characteristics of the 20 Mile March in Schools

Collins outlines seven characteristics of the 20 mile march. So I decided to take the concepts from the stories and reflect on them with an education twist.

1. Clear Performance Markers

Amundsen

Amundsen and his team planned to go an average of 15 miles – 20 miles per day on their journey. No matter the conditions. He placed more than enough flags in the snow to mark their path near the supply stations. He did everything possible to know where he and his team were going and when they would arrive. As a result, his team reached the South Pole on December 15, 1911. After planting the Norwegian flag firmly at their destination, they made preparations for the return journey, knowing that success was not simply arriving but also surviving road back home. They arrived at base camp on the exact date Amundsen planned–January 25th.

Scott:

Scott on the other hand let the conditions drive his pace. He did not lead his team on a strict regimen of travel distance or define daily measures of success for their journey. As a result, his team reached the South Pole more than a month later. On the way back Scott ran out of supplies less than ten miles from their next supply depot.

In Education:

We know it is important to check in and see where our students are in understanding things, but how clear are we about where exactly we want our students to go? What will the evidence of success look like? If we don’t make this clear to both ourselves and our students, how will we know where we/they are and when we/they will arrive? When we have clearly defined measures for success we will know quickly what is working and what isn’t. What will we do when storms come our way and there are challenges to overcome?

One more question: Are we measuring what we hope to see?

2. Self-Imposed Constraints

Amundsen

Ok we know Amundsen went an average of 15-20 miles per day with his team. Amundsen stayed the course even when his team pushed him to go further on days when the conditions were good. He said no, knowing the importance of rest for his team. Amundsen had self-imposed constraints at the upper and lower bounds that kept him on track and his team conditioned for the entire journey.

Scott:

Scott let the conditions and his emotions rule. When conditions were good he went further, pushing his team to the point of exhaustion, yet retreated to his tent complaining about the weather in his journal on days when the conditions weren’t optimal.

In Education:

There is an important balance to be found and self-imposed constraints may be the key.

When we begin taking away things like recess, art, and music under the misguided impression that more “time” focused on core content will result in a deeper understanding of said content–we have lost the balance. Kids learn through play and need time to explore and make connections to apply the things they are learning to their authentic worlds (adults learn this way too). They need time to rest and relax and refresh before they are expected make sense of more information. We can help our students and teachers create self-imposed strategies to implement so they know when to push and when to rest.

What this looks like in action: I know I could stay at school until 7 pm to get all these things done, but maybe it is better for my students and myself if I just do a little bit each day and not push myself to the limits. Find margin in your life and plan for margin in your school day for your students–we all need breaks.

3. Appropriate to Enterprise(or Individual)

Amundsen:

Amundsen did his research. After studying the ways of the Eskimos, Amundsen chose dogs as the main form of transportation for the journey. He also very carefully planned their route, even though it was a path nobody had traveled before. He picked the right methods, routes and details for his team to accomplish their goals, instead of relying on the plans of others.

Scott:

Scott mimicked many of the decisions of another explorer, Ernest Shackleton, who he traveled with in the past. One of the most regrettable decisions was Scott’s choice to use horses for part of the trek and then to man-haul (exactly what it sounds like) the sleds for much of the journey. I don’t know a lot about arctic travel, but that just sounds like a bad idea.

In Education:

Educators need agency to make decisions for their students. Administrators need autonomy to make decisions for their campuses. In most cases, standardization is ineffective and inappropriate for the individual needs of schools and students. Maybe this is why there is so much push back against standardized testing as the ultimate indicator of success in our classrooms today. The 20 Mile chunks of work we implement to reach our goals must be appropriate at the enterprise and individual level. So how are our goals and practices differentiated for our diverse students? How are we giving teachers the space and resources to support a variety of learners in their daily 20 mile march?

4. Largely Within Your Control

Amundsen:

Amundsen was beyond prepared. He knew there were many things that might happen and many things out of his control–like the weather. Amundsen’s average daily distance had to be something achievable on bad weather dates as well as calm sunny days. Supplies could get destroyed, there could be an accident, but he prepared to respond to any of these events with the supplies and plans to overcome the event. When one of his thermometers broke he had another four in his supplies. If they missed a supply depot for any reason, he had enough supplies to go on for miles.

Scott:

Scott was prepared for the perfect journey. When things outside of his control occurred, he was not ready to respond. Scott had one thermometer and cursed when it broke. He cursed the weather and ranted about his misfortunes in his journal instead of responding and leading his team towards safety. He didn’t have the large quantities of reserves if they missed a supply stop and ultimately this lead directly to the unfortunate end for the team when they ran out of supplies and froze to death ten miles from the next supply station.

In Education:

There are lots of things that are beyond our control when it comes to school. You can’t control the fact that your student’s dog ran away the morning of the big test. You can’t change the fact your student’s parents are incarcerated. You can’t change what students did or didn’t learn the year before or what the writing prompt will be on the end of year assessment.

Focus on what you can control and build your 20 mile marches around these things. You can plan, implement, and reflect on lessons that nurture a love for writing every day. You can give students time to read for enjoyment and model this yourself even if it would be easier to use the time to catch up on grading. Let’s not waste time complaining about the circumstances like Scott, but be more like Amundsen and get down to business to support our students.

5. A Proper Timeframe

Amundsen & Scott: As mentioned throughout this post, Amundsen picked a clear, attainable goal to march daily, while Scott was all over the place in his daily distances and timeframes.

In Education:

A good 20 mile march is not too long but not too short. If the timeframe for reaching your edugoals is too short you may fall prey to circumstances outside your control, pulling you off track without time to make up for it. If the timeframe is too long and the check ins are too far off in the distance the march doesn’t have the power it needs.

The successful businesses (known as the 10X companies) Collins references in Great By Choice found this sweet spot of time set to implement goals. The proper timeframe kept goals tangible and in the forefront of the employees minds without being unreasonable to achieve.

6. Designed and Self-Imposed By Enterprise or Individual

Amundsen & Scott: Amundsen carefully researched and implemented plans based on his research of what would work best for his team’s journey. Scott relied on the experiences of others (as mentioned in point 3) to make his decisions, which turned out to be a detrimental decision.

In Education:

Students should play an active role in their learning and teachers an active role in curriculum and learning design and reflection. Let’s give power to our educators and students to design and implement their own 20 mile marches. What if students took part in developing performance indicators for different standards and concepts?

7. Achieved with high consistency

Amundsen & Scott: Amundsen’s team was resolute in their consistency to travel 15-20 miles each day, even if they traveled through storms and challenging conditions. Scott, in contrast, was swayed by a variety of excuses and conditions to go too far or not far enough. Slow and steady wins the race–is the truth at play here.

In Education:

When our 20 mile march goals are achievable with high consistency we gain confidence, we see progress, we build momentum, and we keep on reaching our goals. When we miss the mark and lack the discipline to correct our path, it is too easy to stop, switch to a new plan (project, curriculum, teaching strategy, superintendent etc.).

Last Thoughts & Some Questions:

The 20 Mile March gives me a mental model to organize my thoughts, plans, and actions as I work towards BHAG (big, hairy, audacious goals) a term from another Collins masterpiece, Built to Last. Since latching on to this concept, I visualize each little, daily, 20 mile chunk of work I need to do that will lead me to the goal I have set my mind on. I even add little flag icons in my to do list and map out the breakdown of the seemingly little stuff that needs consistency to get done. This structure and visualization help me plan reasonable goals, stay on track, and get things done.

How do you see these ideas at play in your school?

How can you incorporate these parameters for goal setting with your students?

What is your 20 mile march?